Leg-ups in TIBER testing: Turning roadblocks into learning

Even Red Teams need a leg-up. Here’s our field guide to making TIBER tests smarter and smoother.

Written by:

TIBER tests assess an organisation’s ability to withstand realistic, simulated cyber-attacks. Unlike real threat actors, Red Teams face time limits, ethical constraints, and must avoid undue risk.

A “leg-up” gives them controlled assistance to keep testing on track. In this blog, we share our field guide to leg-ups in TIBER testing and invite the community to discuss their practical and administrative challenges.

Target audience: Anyone involved in a TIBER test, stakeholders, Red, Blue and Control Teams.

TL;DR

Why care: The TIBER-EU framework and its implementations often don’t explain when or how to use leg-ups, so we systemised it.

What’s new: A field guide for properly using leg-ups in TIBER and Red Team tests without sacrificing realism.

Key takeaway: Offer the smallest possible leg-ups, document them rigorously, and keep each scenario moving.

What is a leg-up?

In a TIBER test, the Red Team works with multiple limitations: the test typically covers at least three threat scenarios over 12–16 weeks, and the Red Team must act ethically and responsibly even when simulating ruthless threat actors. When those limits stop a scenario from moving forward, a “leg-up” can be requested as a helping hand that unblocks the Red Team, while keeping the test realistic. It is not a shortcut; it compensates for advantages a real threat actor would have (more time, more resources, fewer constraints) and must be documented.

In TIBER tests, there are multiple teams involved. The Red Team; an external provider doing the actual testing. The Control Team (CT); representing the organisation who is being tested. And the TIBER Cyber Team (TCT); who is a central authority overseeing the TIBER test. All leg-ups must be approved by the TCT, and the Control Team is responsible for preparing leg-ups for the Red Team.

Leg-ups usually take three forms, in order of preference: information the Red Team could have discovered, typically with more time, assistance with a task the Red Team cannot perform under test constraints, or access a real actor could have obtained. A leg-up should provide the minimum help needed to progress the scenario.

Show me the money!

Before we dive into the why and how, we want to show some leg-ups we have used in different scenarios of a recent TIBER test, as these are excellent showcases of typical leg-ups and shows the process in effect.

Example one: Time-saving, information leg-up

Numerous times in this TIBER test, we, the Red Team, asked for information to move faster. In one test scenario, the target was a custom application with almost no public or internal information to be found. We progressed as far as we could, but to continue we needed clarity on what the system actually was. We requested IP addresses, hostnames, and the networks the system(s) resided in and received that from the Control Team. In retrospect, we found that we could have assembled most of this information ourselves, but the time cost justified an information leg-up. We did not want the Blue Team to miss an opportunity to detect our discovery activity, so we absolutely had to try to find the information we were looking for before we received the leg-up, thus giving them a fair chance. This approach legitimised the leg-up and purposefully enabled us to continue testing the scenario.

Example two: Time-saving, assistance leg-up

We had taken control of a Windows server, and observed that certain highly-privileged administrators logged in occasionally. Waiting at length for a specific admin user was not feasible. Instead, we looked up the Active Directory (AD) group memberships of the administrator. Because administrator-level access was fairly consistent across users on this computer, the Control Team was able to recruit an administrator with the exact same group membership and have them log in to the computer. This allowed us to steal the Kerberos ticket (Windows authentication material) of this administrator instead, and move laterally in the environment using this ticket for authentication.

This is a straightforward example of saving time with leg-ups without sacrificing realism. In fact, we re-used this same leg-up in the test, due to the nature of the operation. This approach is better than simply being given the user account, because it required us to use our tradecraft to actually steal the ticket, just as we would if the original user had been logged in. If we had simply received the user’s password, we would not create the same indicators as those created by actually stealing and re-using the Kerberos ticket.

Example three: Resource (and time) saving, access leg-up

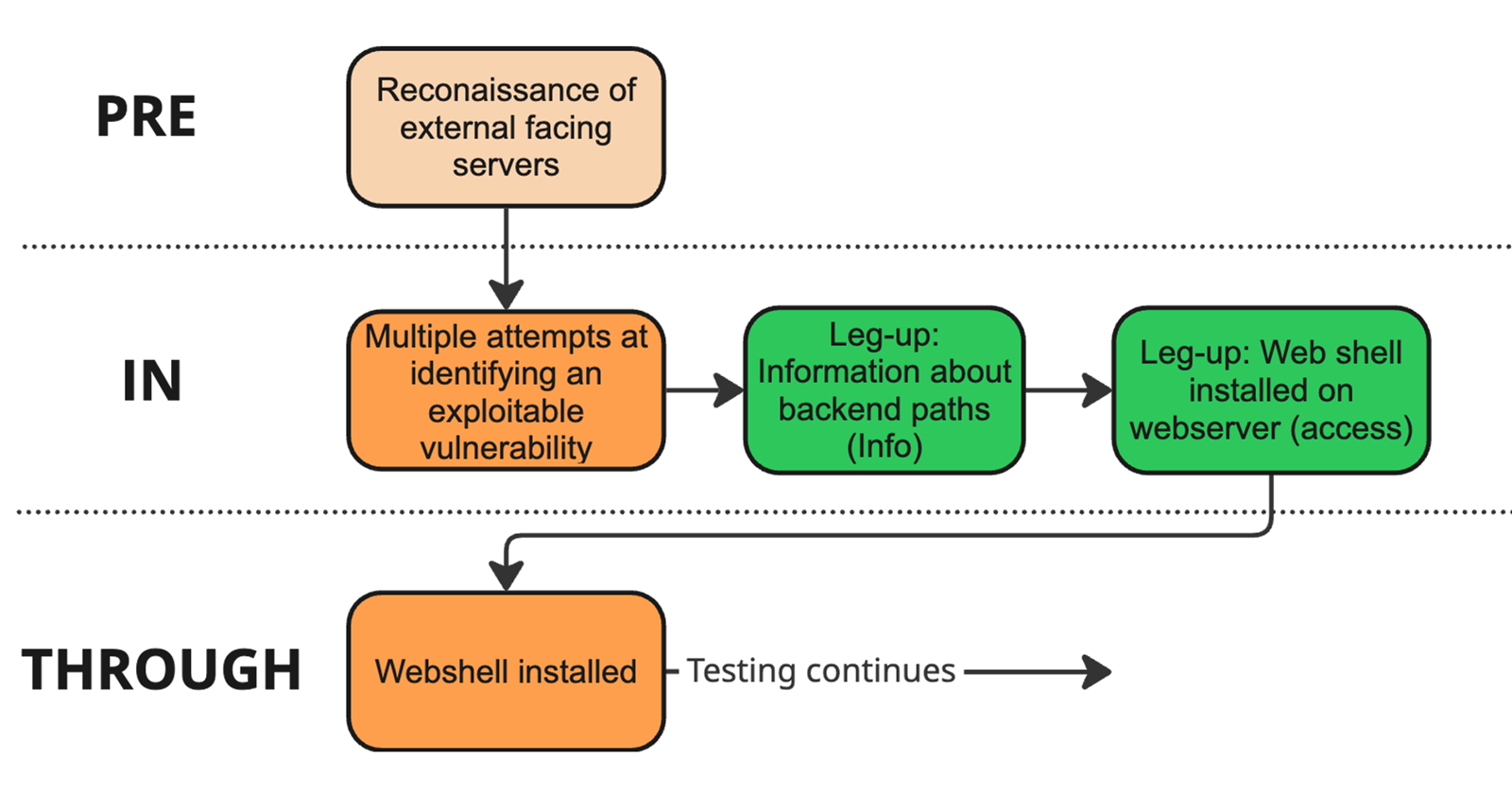

In this scenario, we had not yet breached the perimeter. The actor we were emulating typically compromises an Internet-facing IIS server and plants a web shell, so that was our objective. After weeks of attempts on a very small external scope - only a few relevant IIS hosts - we had not found any viable vulnerability to exploit. The first leg-up we proposed and received included some information about backend file paths to explore some previously undiscovered endpoints, but this also led to nowhere.

Given the threat intelligence and prior incidents showing actors of this calibre breach web servers and deploy web shells, we chose to propose an access leg-up: having the Control Team deploy a web shell on our behalf. This is about as far as we are willing to stretch when asking for leg-ups, but since it aligned so well with what a real threat actor could achieve with more time and resources, we decided to request it.

If your immediate reaction is, “but that is cheating,” remember the goal of a TIBER test is not to prove world-class zero-day hunting, or emulate a threat actor down to their every move, but rather maximise learning for the organisation.

Exploring the consequences of a web-shell foothold would produce far more value than burning the remaining test time on unlikely bugs or restarting the intrusion process with another approach. Testing the organisation’s detection and response given a compromise of an Internet-facing asset with a web shell deployed is not only interesting, but an often-unexplored area of offensive security testing.

With this reasoning, the TCT agreed to let the Control Team deploy a web shell for us to use. We designed a novel, stealthy web shell with capabilities similar to those of nation-state groups, and used it to complete the entire test scenario. This example highlights how the leg-up process can be used to facilitate interesting test scenarios, even if it means sacrificing some realism. The particular trade-off made for this leg-up was worth it for the extensive scenario we then were able to test.

Leg-up field guide

To understand how we work with leg-ups, here is how we approach their design and approval in a systematic manner.

Leg-up reasoning

To identify what reasons there are for granting leg-ups, a simple assessment reveals the differences between a real threat group and a Red Team:

| Category | Advanced Threat Actor | Red Team |

| Time | 6 months – 2 years | 4-6 weeks (per scenario) |

| Resources |

Funded by nation state or organised crime. |

Commercial tools available, but budget-constrained. |

| Ethics | Acts unethically, for example using COVID-19 as a pretext. | Has to act ethically to avoid causing more damage than they may be preventing. |

| Operational and IT risk | Is not concerned with IT risk and may in some cases accept detection, like in a ransomware scenario. | Cannot cause undue risk on the organisation, and must try not to perform actions that could reveal the entire TIBER test. |

To summarise, these are the primary reasons for providing leg-ups, all grounded in compensating for the difference between the Red Team and threat actor:

- Time-saving leg-ups – compensate for the difference in available time.

- Resource-saving leg-ups – compensate for the differences in available resources.

- Ethical limitation leg-ups – compensate for the different code of ethics.

- Operational and IT risk leg-ups – compensating for activities that involve risk of revealing the test (operational security) or cause undue IT risk for the organisation.

Leg-up types

With reasons for why leg-ups are given firmly established, let’s look at what types of leg-ups are available. Leg-ups are defined by a type, which describes what they practically involve. These are the types of leg-ups we use in TIBER tests:

- Information leg-ups – providing information about systems.

- Assistance leg-ups – assisting with physical tasks.

- Access leg-ups – giving direct access to systems or accounts.

Leg-ups should be granted by the Control Team, and approved by TCT, in a prioritised order. Within each reason, choose the type that gives the minimum help needed. Informational leg-ups are considered the “smallest” leg-up, and are normally easy to argue for (RT), approve (TCT) and provide (CT). Assistance leg-ups are preferred after information, as they provide the Red Team with some help without giving direct access to a system or account. Access leg-ups typically give direct access to for example a system or set of account credentials, giving the Red Team access they have not acquired themselves, and are therefore the least preferable type of leg-up.

Leg-ups to avoid

Certain leg-ups break realism or wipe out learning and therefore are off-limits:

- Disabling security controls, or reducing the security posture of the organisation.

- Providing direct access to target systems for a test scenario (“flags”).

- Uncontrolled access that could trigger real business impact (unless a subject-matter expert can guide the RT).

Approving and activating leg-ups

According to the TIBER-EU framework, all leg-ups have to be approved by the TCT of the test. To make it as simple as possible, we frame the leg-ups in this manner, as a discussion, typically had in fixed frequency meetings with the Control Team and the TCT:

- Present scenario – explain why the Red Team is blocked (time, resources, ethics, risk).

- Present the suggested leg-up – what you’re asking for and why a real actor could reasonably obtain it.

- Present value – describe how the leg-up can unlock new learning, increase progress, or enable further testing.

- Obtain approval – TCT must approve all leg-ups, and CT must be able to provide them.

- Document – the leg-up must be documented in detail.

Documenting leg-ups

Below, we provide a template for rigorously documenting leg-ups. In the final report, we describe how each leg-up was used in each scenario timeline. We also include the full table of all leg-ups as an appendix for each scenario.

| Code | LU-A-01 |

| Leg-up | Information about target systems for the OUT phase: – IP addresses, hostnames, networks, account IDs |

| Reason | The Red Team is out of time for discovery activity, and needs to make progress in the current test phase. |

| Type | Information |

| Compensates for | Time spent performing further discovery activity in the environment. |

| Activation requirement | The Red Team has not identified the information within one week of discovery activity. |

| Activation status | Approved |

Activation status is convenient to track for all involved parties. Status we typically use are:

- Not approved - add a comment on why if possible.

- Approved, but not received yet

- Approved and received

- Retracted - if the Red Team decides they don’t need it.

TIBER tests typically have the Red Team test multiple attack scenarios. Leg-ups must be separate per scenario and a leg-up given in one scenario cannot be used directly in another, even if it is identical. A great tip to avoid mixing up leg-ups across scenarios is to use a consistent, codified naming convention for leg-ups. We recommend LU- [Scenario Code]- [##] – e.g., LU-A-01 for the first leg-up in Scenario A. Having codes keeps planning, approving and ultimately reporting how leg-ups are used in the test aligned.

Practical tips for Control Teams

The Control Team is responsible for actually procuring the leg-ups. To avoid delays, revealing the test or encountering challenges with the practicalities of leg-ups, here are some tips based on our experience:

- Prepare early – some leg-ups (accounts, MFA tokens, implants) take weeks to stage. Have the RT propose leg-ups sooner rather than later.

- User accounts and end-user devices – create realistic names and roles, avoid obvious “pentest” markers like “Test Account”. Follow standard procedures for account and device procurement, and avoid tying it to employees known to work with security testing if possible.

- Administrator accounts – if high-privilege access is needed, prepare credentials or keep an IT administrator on standby who can provide assistance or access leg-ups.

- Hardware delivery – ship devices to neutral addresses, avoid directly referencing the RT provider.

Leg-up examples

Reviewing our battle tested leg-ups

Now within the guidelines of our approach, we can categorise the leg-ups we described earlier, and we see they can all be reasoned and categorised appropriately. For documentation purposes, we describe all our leg-ups with much more detail than what is listed below.

| Leg-up description | Reason(s) | Type | Compensates for | Activation requirement |

| Host information about target system for the OUT phase, including IP addresses, hostnames and networks. | Time-saving | Information |

Time being spent on additional discovery activity. |

One full week of discovery activity has been attempted without success. |

|

Have an administrator user log in to a RT compromised server so they can steal their Kerberos ticket. |

Time-saving | Assistance |

Time spent waiting for the specific administrator to log in to the system. |

The RT have proven they have the capability to steal Kerberos tickets of logged-in accounts. |

| Deploy a web shell for the Red Team to compensate for not being able to discover and exploit a file upload or remote code execution vulnerability on the Internet-facing perimeter. |

Time-saving Resource-saving |

Access |

Not being able to identify an exploitable vulnerability in the given time frame. |

Two weeks of external testing without success. Information leg-up yields no results. |

Other example leg-ups

These are some examples of leg-ups that could be used as inspiration, both during planning and testing. Here we added what the compensating factor is, and what the activation trigger for a leg-up should be.

|

Leg-up description |

Reason(s) | Type | Compensates for | Activation trigger |

| CT hands over target system IP addresses, so that enumeration doesn’t stall the test | Time | Info | Time being spent on additional discovery provides limited learning value for the organisation | More than one full week spent on discovery activities without results |

| CT assists with “clicking” as a phishing victim would |

Time Ethics |

Assistance | RT cannot expedite phishing operations with unethical pretexts like for instance death | Phishing blocked by low click-rate, not by security controls |

| CT provides plaintext credentials for an account |

Time Resources IT risk Operational |

Access | A strong argument must be made for why this leg-up should be granted, given specific circumstances. For example, that resetting the account’s password to take control of it would cause great IT risk | Typically, only used as a last resort if testing stalls completely with no other options to make progress |

| Cracking an encrypted password hash |

Resources IT risk |

Info | Threat actors can rent expensive hash-cracking computing power; the RT often can’t due to IT risk and budget constraints | RT and CT believe a hash is crackable with enough GPU hours |

| Red Team is given the name of the Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) product in the target environment | Resources | Info | RT cannot perform actions that risk revealing the TIBER test. Can assume that threat actor is able to obtain this information | Red Team has tried to, but has not acquired this information. Or, RT repeatedly fails to bypass EDR |

|

A member of the Control Team with system knowledge assists/guides the Red Team in the OUT phase |

IT risk | Assisstance | Needed to prevent undue risk on target (business specific) systems while still testing these systems | The Control Team deems it necessary to mitigate the IT risk involved with allowing the RT to test these systems on their own |

Key takeaways for Red and Control Teams

Use leg-ups actively in Red and TIBER tests, but make sure they are well reasoned. Document them rigorously, and always choose the lightest leg-up that still drives the scenario forward. Leg-ups are minimal, documented pieces of help, not shortcuts for a lazy Red Team. Prioritise information, then assistance, then access leg-ups. Done right, leg-ups keep a TIBER test realistic, on-schedule and rich in learning opportunities.

Questions?