How to detect and prevent advanced web shells: Part 3

Modern detection strategies often overlook stealthy web shells and this is how you close the detection gap.

Written by:

In part one of this series, we explained how web shells fit into TIBER testing and why they remain a relevant threat actor technique. In part two, we described how the mnemonic Red Team built and operated a custom web shell that mirrored advanced tradecraft in a TIBER test. In this third and final post, we shift focus to the defender’s perspective. We describe how to prevent advanced web shells from being deployed, and how to detect and contain them if they are.

This three-part blog series has three goals:

- Part 1/3 - Explain how web shells fit into Red Team and TIBER testing.

- Part 2/3 - Show how advanced threat actor tradecraft can be replicated in a controlled test through a custom web shell implementation.

- Part 3/3 - Provide practical guidance on how to prevent and detect web shells.

Target audience: Detection engineers, Purple and Red Team operators, security practitioners.

TL;DR

Why care: Modern detection strategies often overlook stealthy web shells, which remain a common technique in advanced cyber intrusions.

What’s new: A custom, threat intelligence-driven web shell built for a TIBER test showed how advanced shells bypass signature-based detection.

Key takeaway: Defenders need detection and prevention coverage against web shells that goes beyond endpoints, with visibility at the application, file system, and network layers.

Detecting and preventing advanced web shells

Detecting a custom web shell is fundamentally different from identifying a commodity web shell. The static strings, predictable request patterns, and known filenames defenders often rely on may be absent when the shell is tailored to its target and shaped to blend into normal traffic. Signature-based scanning alone is rarely sufficient, so detection should also focus on identifying the web shell through the effects of it being used in an environment.

A detection gap

Detection coverage in most organisations is still heavily weighted toward phishing, endpoint malware and lateral movement in internal networks. External-facing web infrastructure often receives less continuous monitoring, and scanning, if any, tends to focus on known web shells like China Chopper or Godzilla. These signatures work on commodity tooling but fail against custom web shells designed to blend into the application’s normal structure and behaviour. In this blind spot, a single well-placed web shell can operate for weeks or months without being detected.

Why direct detection is difficult

A capable threat actor will make deliberate design choices to evade traditional detection, including:

- Using filenames and paths that match legitimate application structure.

- Shaping HTTP requests to match normal endpoints and traffic patterns.

- Serving valid application content to unauthenticated requests, hiding the true interface.

- Avoid spawning new processes like cmd.exe.

Prevention and hardening

The first line of defence is to reduce the chance of a web shell ever being deployed. Hardening measures do not guarantee that a web shell installation will be prevented, but they narrow the attacker’s options and make exploitation harder and riskier. Preventive controls also limit what an attacker can do if they manage to deploy a web shell.

Vulnerability management

Fixing exploitable bugs and addressing weaknesses in Internet-exposed applications takes away the easiest paths attackers rely on to install web shells in the first place.

- Validate all user input to reduce local and remote file inclusion or file upload vulnerabilities.

- Conduct regular vulnerability scanning, application fuzzing, code reviews, and server network analysis.

Configuration management

Hardening default configuration and keeping systems patched can limit the opportunities of an attacker that has successfully deployed a web shell, for example by preventing privilege escalation.

- Keep both the host operating system and all web applications fully updated to close known vulnerabilities.

- Apply secure configuration baselines: disable unnecessary services and ports, restrict access to administration panels, and avoid default credentials.

Network segmentation and filtering

Isolating web servers from the internal network in a DMZ keeps a compromise contained and makes attempts at tunnelling traffic (as we demonstrated in Part 2) easier to detect.

- Use a DMZ to isolate web-facing systems from the internal network and log all traffic crossing the boundary.

- Use a reverse proxy or web application firewall (WAF) to restrict URL paths to known legitimate ones.

Account and privilege restrictions

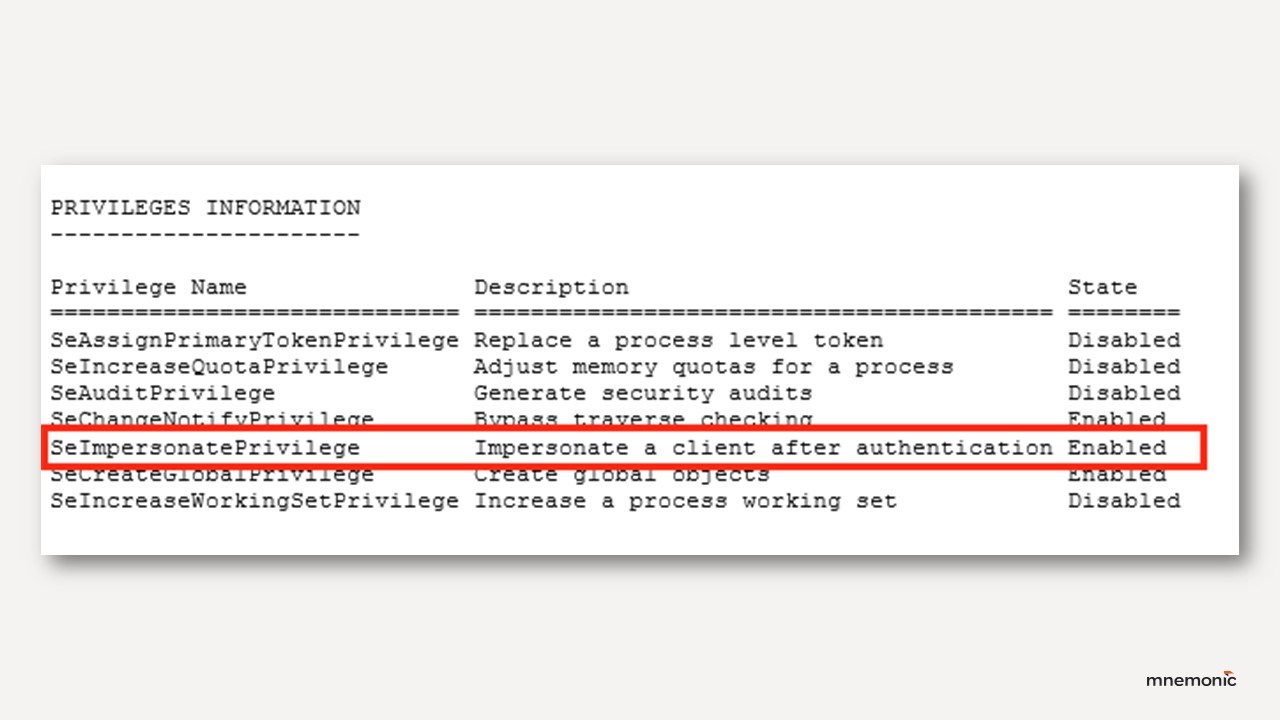

Restricting what the web server account can actually do limits how far an attacker can get even if their web shell bypasses other defences. This is an important control because by default IIS service accounts runs with privileges that enable privilege escalation by default.

- Enforce a least-privilege model on the web server to limit escalation opportunities and control where files can be created or executed.

- Review and restrict privileges assigned to IIS Application Pool identities. Where impersonation is not required, use dedicated low-privilege service accounts instead of default virtual accounts, and remove SeImpersonatePrivilege and SeAssignPrimaryTokenPrivilege from those accounts to reduce privilege escalation risk (see Decoder’s “Hands off my IIS accounts” for methodology).

Detection and response

No prevention is perfect, and being able to detect web shells is crucial. Detection requires visibility into both the web shell and its operational effects in the target environment. These controls focus on detecting both the web shell and what it is used for.

Process and memory monitoring

Watching process relationships and baselining what processes normally do may provide indicators when something unusual is loaded straight into memory.

- Monitor .NET runtime telemetry (AMSI, CLR ETW) for suspicious in-memory assembly loads in processes like w3wp.exe.

- Watch for suspicious memory contents such as injected assemblies, unexpected code segments, or active socket handles to unusual destinations.

Behavioural indicators

Look for anomalies such as strange commands, unknown traffic, or new files in unexpected places.

- Monitor for behavioural indicators from CISA’s guidance: files in unexpected locations, suspicious commands from the web server process, anomalous network traffic from non-executable files, abnormal login patterns between internal and DMZ systems.

Application layer telemetry

Logging IIS and web app activity at the same level as endpoints gives visibility into odd request patterns.

- Instrument and log web servers and their software to the same standard as endpoints.

- Enable Microsoft-IIS-Configuration/Operational logging; alert on module additions/removals (Event ID 29) or web.config changes (Event ID 50) (Microsoft).

- Harden against request/response tampering via advanced IIS logging and deep inspection for anomalies in headers, methods, or bodies.

File system monitoring

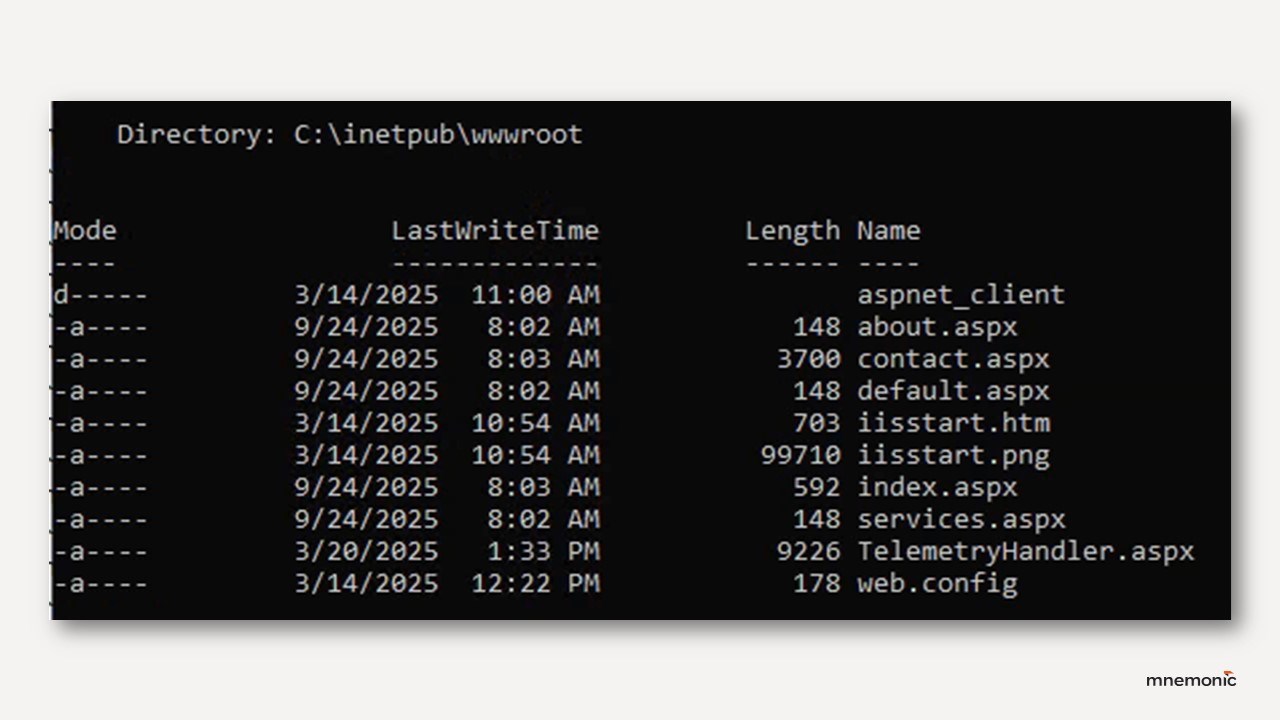

Watching for new or modified files in web roots is still one of the simplest ways to catch web shells right as they are written to disk.

- Use file integrity monitoring (FIM) on web root directories to detect unexpected file changes or suspicious timestamps.

Network telemetry

Unusual connections from a web server process are often the first sign that a web shell is being used to perform network connections, for example when serving as a tunnel for a C2 agent.

- Hunt for unusual outbound or internal connections initiated by the web server process.

- Detect abnormal HTTP patterns, such as repeated POST requests of consistent size to a single endpoint.

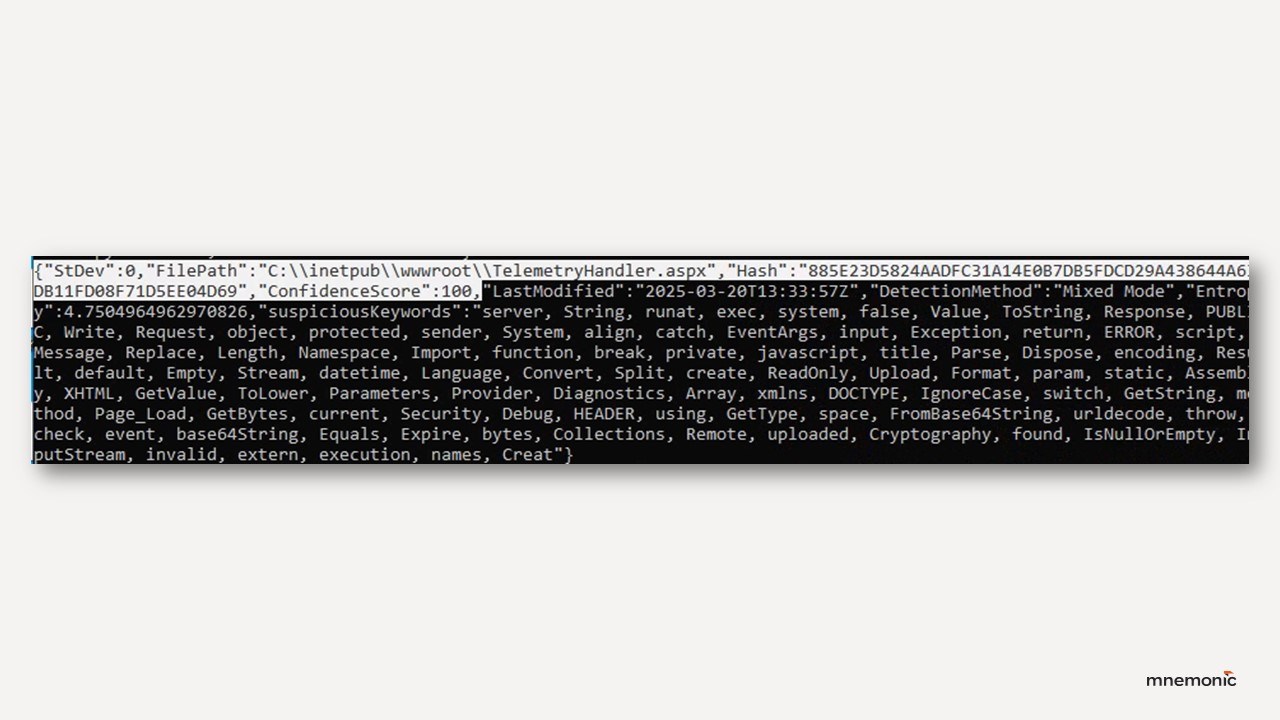

Code-based detection and testing

Running scans and replaying shell behaviour in controlled huntshelps confirm if defences would actually catch it.

- Use tools like Splunk’s ShellSweep to detect potential web shells through code analysis rather than static signatures.

- Replay realistic web shell behaviour in threat-hunting and Purple Team tests to validate log coverage and detection capabilities.

Conclusion

A single well-designed web shell can persist undetected if detection is based only on known indicators. Combining preventive hardening, file integrity monitoring, process and network telemetry, and code-based scanning significantly improves the likelihood of detecting both web shells and their activity before they can be used to cause significant impact.

In this series, we have showed why web shells matter in TIBER testing, how a custom web shell can be built to mirror advanced threat actor tradecraft, and finally how defenders can counter them. The final lesson is that both prevention and detection are possible, but only if organisations look beyond static signatures and commodity indicators. Visibility into the application layer, close monitoring of web server processes, and awareness of post-exploitation activity are essential. By incorporating realistic, stealthy web shell scenarios into Red and Purple Team testing, defenders can close gaps before a real threat actor exploits them.

Chris Risvik